Palestinian refugee

| Total 2008 population (including descendants): | 4.62 million [1] |

|---|---|

| UNRWA estimated refugees from 1947: | 711,000[2] |

| Regions with significant populations: | Gaza Strip, Jordan, West Bank, Lebanon, Syria |

| Languages: | Arabic |

| Religions: | Sunni Islam, Greek Orthodoxy, Greek Catholicism, other forms of Christianity |

Palestinian refugees or Palestine refugees are the people and their descendants, predominantly Palestinian Arabic-speakers, who fled or were expelled from their homes during and after the 1948 Palestine War, Within that part of the British Mandate of Palestine that after that war became the territory of the State of Israel, and the Palestinian territories.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), an organ of the United Nations created to aid the displaced from the 1948 defines a Palestinian refugee as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict". UNRWA's definition of a Palestinian refugee also covers the descendants of persons who became refugees in 1948[3] regardless of whether they reside in areas designated as refugee camps or in other permanent communities.[4]

[5] Descendants of Palestinian refugees under the authority of the UNRWA are the only group to be granted refugee status on the basis of descent alone.[6] Based on the UNRWA definition, the number of Palestine refugees has grown from 711,000 in 1950[2] to over four million registered with the UN in 2002.

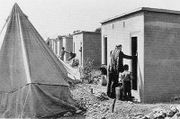

Some displaced Palestinians resettled in other countries where their situation is often precarious. Many remained refugees and continue to reside in refugee camps, including in the Palestinian territories.

Contents |

Origin of the Palestinian refugees

Refugees from 1948 War

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, around 750,000 out of 900,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from the territories that became the State of Israel.[2] The causes and responsibilities of the exodus are a matter of controversy among historians and commentators of the conflict.[7] Whereas historians now agree on most of the events of that period, there remains disagreement as to whether the exodus was the result of a plan designed before or during the war by Zionist leaders, was the result of a plan designed before or during the war by Arab leaders, or was an unintended consequence of the war.[8]

Between December 1947 and March 1948, around 100,000 Palestinian Arabs fled. Among them were many from the higher and middle classes from the cities, who left voluntarily, expecting to return when the Arab states took control of the country.[9] When the Haganah went on the offensive, between April and July, a further 250,000 to 300,000 Palestinian Arabs left or were expelled, mainly from the towns of Haifa, Tiberias, Beit-Shean, Safed, Jaffa and Acre, which lost more than 90 percent of their Arab inhabitants.[10] Expulsions took place in many towns and villages, particularly along the Tel-Aviv-Jerusalem road[11] and in Eastern Galilee.[12]

About 50,000-70,000 inhabitants of Lydda and Ramle were expelled towards Ramallah by the Israel Defence Force during Operation Danny,[13] and most others during operations of the IDF in its rear areas.[14] During Operation Dekel, the Arabs of Nazareth and South Galilee were allowed to remain in their homes.[15] Today they form the core of the Arab Israeli population. From October to November 1948, the IDF launched Operation Yoav to remove Egyptian forces from the Negev and Operation Hiram to remove the Arab Liberation Army from North Galilee during which at least nine massacres of Arabs were carried out by IDF soldiers.[16] These events generated an exodus of 200,000 to 220,000 Palestinian Arabs. Here, Arabs fled fearing atrocities or were expelled if they had not fled.[17] After the war, from 1948 to 1950, the IDF expelled around 30,000 to 40,000 Arabs from the borderlands of the new Israeli state.[18]

Refugees from Six-Day War

|

As a result of the Six-Day War, around 280,000 to 325,000 Palestinians fled[19] the territories occupied by Israel, including the demolished Palestinian villages of Imwas, Yalo, Bayt Nuba, Surit, Beit Awwa, Beit Mirsem, Shuyukh, Jiftlik, Agarith and Huseirat, and the "emptying" of the refugee camps of ʿAqabat Jabr and ʿEin Sulṭān.[20][21]

UNRWA definition

Whereas most refugees are the concern of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), most Palestinian refugees - those in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon,and Syria, - come under the older body UNRWA. On 11 December 1948, UN Resolution 194 was passed. It called, among other things, for the return of refugees from Arab-Israeli hostilities then ongoing, although it did not specify only Arab refugees. Resolution 302 (IV) of 8 December 1949, set up UNRWA specifically to deal with the Palestinian refugee problem. Palestinian refugees outside of UNRWA's area of operations do fall under UNHCR's mandate, however.

The United Nations never formally defined the term Palestinian refugee. The definition used in practice evolved independently of the UNHCR definition, established by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The UNRWA defines a Palestine refugee as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948, ands 1967 conflicts,"[22] This definition has generally only been applied to those who living in one of the countries where UNRWA provides relief. The UNRWA also registers as refugees descendants in the male line of Palestine refugees, and persons in need of support who first became refugees as a result of the 1967 conflict. The UNRWA definition in practice is thus both more restrictive and more inclusive than the 1951 definition. For example, the definition excludes persons taking refuge in countries other than Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, but includes descendants of refugees as well as the refugees themselves. In many cases UNHCR provides support for the children of refugees too.

Persons receiving relief support from UNRWA are explicitly excluded from the 1951 Convention, depriving them of some of the benefits of that convention such as some legal protections. However, a 2002 decision of UNHCR made it clear that the 1951 Convention applies at least to Palestinian refugees who need support but fail to fit the UNRWA working definition.[23] A 1952 UNRWA document says that the natural rate of increase in the refugee population was estimated as 22,000 individuals per year, although precise figures are unobtainable.[24] Today, about 30% of those registering with the UNRWA as Palestine refugees are living in areas designated as refugee camps.[25]

Critics of UNRWA say that the present definition give Palestine refugees a favored status when compared with other refugee groups, which the UNHCR defines in terms of nationality as opposed to a relatively short number of years of residency.[26] Defenders of UNRWA respond that it is precisely the stateless status of the Palestinian Arabs under British mandate in 1948 that made it necessary to create a definition of refugee based on other criteria than nationality. Historians, such as Martha Gellhorn and Dr. Walter Pinner, have also blamed UNRWA for distortion of statistics and even of sheer fraud. Pinner wrote in 1959 that the actual number of refugees then was only 367,000.[27]

Refugee statistics

The number of Palestine refugees varies depending on the source. For 1948-49 refugees, for example, the Israeli government suggests a number as low as 520,000 as opposed to 850,000 by their Palestinian counterparts. The UNRWA cites 726,000 people.[28]

The number of descendents of Palestinian refugees by country as of 2005 were as follows:

- Jordan 1,827,877 refugees

- Gaza 986,034 refugees

- West Bank 699,817 refugees

- Syria 432,048 refugees

- Lebanon 404,170 refugees

- Saudi Arabia 240,000 refugees

- Egypt 70,245 refugees[1]

Jordan refugees

1,951,603 Palestinian refugees in Jordan, of whom 338,000 are still living in refugee camps [29]. Jordan granted most of the Palestinian refugees the Jordanian citizenship in 1950. The percentage of Palestinian refugees living in refugee camps to those who settled outside the camps is the lowest of all UNRWA fields of operations. Palestinian refugees are allowed access to public services and healthcare, as a result, refugee camps are becoming more of poor city suburbs than refugee camps. Most refugees moved out of the camps to other parts of the country reducing the number of refugees in need of UNRWA services to only 338,000. This caused UNRWA to reduce the budget allocated to Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. Former UNRWA chief-attorney James G. Lindsay says: "In Jordan, where 2 million Palestinian refugees live, all but 167,000 have citizenship, and are fully eligible for government services including education and health care." Lindsay suggests that eliminating services to refugees whose needs are subsidized by Jordan "would reduce the refugee list by 40%." [30][31]

Palestinians who moved from the West Bank (whether refugees or not) to Jordan, are issued yellow ID cards to distinguish them from the Palestinians of the "official 10 refugee camps" in Jordan. Since 1988, thousands of those yellow-ID card Palestinians had their Jordanian citizenship revoked in order to prevent the possibility that they might become permanent residents of the country. Jordan's Interior Minister Nayef al-Kadi said

"Our goal is to prevent Israel from emptying the Palestinian territories of their original inhabitants," the minister explained, confirming that the kingdom had begun revoking the citizenship of Palestinians. "We should be thanked for taking this measure," he said. "We are fulfilling our national duty because Israel wants to expel the Palestinians from their homeland."[32]

It is estimated that over 40 000 Palestinians have been affected in the preceding months.[33]

India

The first group of Palestinian refugees from Iraq arrived in India in March 2006. Generally, they were unable to find work in India as they spoke only Arabic though some found employment with UNHCR's non-governmental partners. All of them were provided with free access to governmental hospitals. Of the 165 Palestinian refugees from Iraq in India, 137 of them found clearance for resettlement in Sweden.[34]

Lebanon

Over 400,000 Palestinian refugees live in Lebanon, who are deprived of certain basic rights. Lebanon barred Palestinian refugees from 73 job categories including professions such as medicine, law and engineering. They are not allowed to own property, and even need a special permit to leave their refugee camps. Unlike other foreigners in Lebanon, they are denied access to the Lebanese healthcare system. The Lebanese government refused to grant them work permits or permission to own land. The number of restrictions has been mounting since 1990.[35] In June 2005, however, the government of Lebanon removed some work restrictions for a few Lebanese-born Palestinians, enabling them to apply for work permits and work in the private sector.[36] In a 2007 study, Amnesty International denounced the "appalling social and economic condition" of Palestinians in Lebanon.[37]

Lebanon gave citizenship to about 50,000 Christian Palestinian refugees during the 1950s and 1960s. In the mid-1990s, about 60,000 refugees who were Shiite Muslim majority were granted citizenship. This caused a protest from Maronite authorities, leading to citizenship being given to all the Palestinian Christian refugees who were not already citizens.[38] there are about 350,000 non-citizen Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

The Lebanese Parliament is divided on granting Palestinian rights. While many Lebanese parties call for improving the civil rights of Palestinian refugees, others raise concerns of naturalizing the mainly Muslim population and the disruption this might cause to Lebanon’s sectarian balance.[39]

Positions on the problem and right of return

| Part of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and Arab–Israeli conflict series |

|||||

| Israeli–Palestinian Peace Process |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Negotiating Parties | |||||

| Israel | Palestinians | ||||

| History | |||||

| Camp David Accords · Madrid Conference Oslo Accords / Oslo II · Hebron Protocol Wye River / Sharm el-Sheikh Memoranda 2000 Camp David Summit · Taba Summit Road Map · Annapolis Conference |

|||||

| Primary Negotiation Concerns | |||||

| Final borders · Israeli settlements · Refugees (Jewish, Palestinian Arab) · Security concerns Status of Jerusalem · Water |

|||||

| Secondary Negotiation Concerns | |||||

| Antisemitic incitements Israeli West Bank barrier · Jewish state Palestinian political violence Places of worship |

|||||

| Palestine Current Leaders Israel | |||||

| Mahmoud Abbas Salam Fayyad |

Shimon Peres Benjamin Netanyahu |

||||

| International Brokers | |||||

| Diplomatic Quartet (United Nations, United States, European Union, Russia | |||||

| Arab League (Egypt, Jordan) · United Kingdom · France | |||||

| Other Proposals | |||||

| Arab Peace Initiative · Elon Peace Plan Lieberman Plan · Geneva Accord · Hudna Israel's unilateral disengagement plan Israel's realignment plan Peace-orientated projects · Peace Valley · Isratin · One-state solution · Two-state solution · Three-state solution · Middle East economic integration |

|||||

| Major projects, groups and NGOs | |||||

| Peace-oriented projects · Peace Valley · Alliance for Middle East Peace · Aix Group · Peres Center for Peace | |||||

|

|||||

On 11 December 1948 the General Assembly discussed Bernadotte's report and resolved: "that refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbour should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date.[40]" This resolution has been annually re-affirmed by the UN since, but Israel says that the resolution is non-binding, does not mention a "right" anywhere, and argues that the "live in peace" condition has not been met and has prevented the return of any refugees.

Israeli views

The Israeli declaration of independence appealed "to the Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel to preserve peace and participate in the upbuilding of the State on the basis of full and equal citizenship" [41]. Similarly the Jewish Agency had promised to the UN before the Declaration that Palestinian Arabs would become full citizens of the State of Israel[42]. The Israeli Knesset (parliament) does not consider the Declaration to have the power of law, and Israel does not in practice consider the refugees to be Israeli citizens. The 1947 Partition Plan determined citizenship based on residency, such that Arabs and Jews residing in Palestine but not in Jerusalem would obtain citizenship in the state in which they are resident. Professor of Law at Boston University Susan Akram, Omar Barghouti and Ilan Pappé have argued that Palestinian refugees from the envisioned Jewish State were entitled to normal Israeli citizenship based on laws of state succession[43].

Arab states

The Arab League has instructed its members to deny citizenship to Palestinian Arab refugees (or their descendants) "to avoid dissolution of their identity and protect their right to return to their homeland".[44]

Tashbih Sayyed, a Shi’ite Pakistani scholar, criticized Arab nations of making the children and grandchildren of Palestinian refugees second class citizens in Lebanon, Syria, or the Gulf States, and said that the refugees "cling to the illusion that defeating the Jews will restore their dignity".[45]

Palestinian views

Palestinian refugees claim a right of return. Their claim is based on Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which declares that "Everyone has the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country." Although all Arab League members at the time- Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen- voted against the resolution,[46] they also cite article 11 of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, which "Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return [...]."[47] However Resolution 194 is a nonbinding assembly resolution, and it is currently a matter of dispute whether the resolution referred only to refugees in 1948, or additionally to their descendants. The Palestinian National Authority supports this claim, and has been prepared to negotiate its implementation at the various peace talks. Both Fatah and Hamas hold a strong position for a right of return, with Fatah being prepared to give ground on the issue while Hamas is not.[48]

Compromise proposals

Since 1970, several attempts have been made to meet the terms of both Israel and the Palestinian people. Most recently, the government of Israel, in collaboration with the United Nations, attempted to accommodate the refugee concern by facilitating the creation of an independent Palestinian state. This was negotiated during the Oslo Accords. However, events since then have halted the phasing process and made the likelihood of a future sovereign Palestinian state uncertain.[49][50]

Further reading

- Bowker, Robert P. G. (2003). Palestinian Refugees: Mythology, Identity, and the Search for Peace. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-58826-202-2

- Gelber, Yoav (2006). Palestine 1948. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-075-0.

- Gerson, Allan (1978). Israel, the West Bank and International Law. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-3091-8

- McDowall, David (1989). Palestine and Israel: The Uprising and Beyond. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-289-9.

- Morris, Benny (2003). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7

- Pappe, Ilan (2006). The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, London and New York: Oneworld, 2006. ISBN 1-85168-467-0

- Segev, Tom (2007) 1967 Israel, The War and the Year that Transformed the Middle East Little Brown ISBN 978-0-316-72478-4

- Seliktar, Ofira (2002). Divided We Stand: American Jews, Israel, and the Peace Process. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-97408-1

- Jewish exodus from Arab lands

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Total registered refugees per country and area" (PDF). United Nations. 2008. http://www.un.org/unrwa/publications/pdf/rr_countryandarea.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the Period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950". United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine. 1950. http://unispal.un.org/unispal.nsf/b792301807650d6685256cef0073cb80/93037e3b939746de8525610200567883?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ "Palestine Refugees". UNRWA. http://www.unrwa.org/etemplate.php?id=86. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Ruth Lapidoth (2002). "Legal aspects of the Palestinian refugee question". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. http://www.jcpa.org/jl/vp485.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ Adam Keller of the Tel-Aviv based Gush Shalom movement noted that "The recognition of decendants of Palestinian refugees as being refugees themselves, without a time limit, is an ironic emulation of the Zionist Movement's claim that all Jews are "refugees", whose ancestors left Eretz Yisrael nearly 2000 years ago. This claim was recognised by the International Community, in authorising the Zionists to create a Jewish state; it is natural that a similar right be recogised for the Palestinians displaced due to the Zionist claim (Lecture in October 2008 Tel Aviv panel discussion on the history of the conflict.

- ↑ "Publications/Statistics". UNRWA. 2006. http://www.un.org/unrwa/publications/index.html. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ Shlaim, Avi, "The War of the Israeli Historians." Center for Arab Studies, 1 December 2003 (retrieved 17 February 2009)

- ↑ Benny Morris, 1989, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, Cambridge University Press; Benny Morris, 1991, 1948 and after; Israel and the Palestinians, Clarendon Press, Oxford; Walid Khalidi, 1992, All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948, Institute for Palestine Studies; Nur Masalha, 1992, Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of "Transfer" in Zionist Political Thought, Institute for Palestine Studies; Efraim Karsh, 1997, Fabricating Israeli History: The "New Historians", Cass; Benny Morris, 2004, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press; Yoav Gelber, 2006, Palestine 1948: War, Escape and the Palestinian Refugee Problem, Oxford University Press; Ilan Pappé, 2006, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, OneWorld

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), pp.138-139.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), p.262

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), pp.233-240.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), pp.248-252.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), pp.423-436.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), p.438.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), pp.415-423.

- ↑ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, p245.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), p.492.

- ↑ Benny Morris (2003), p.538

- ↑ Bowker, 2003, p. 81.

- ↑ Gerson, 1978, p. 162.

- ↑ UN Doc A/8389 of 5 October 1971. Para 57. appearing in the Sunday Times (London) on 11 October 1970, where reference is made not only to the villages of Jalou, Beit Nuba, and Imwas, also referred to by the Special Committee in its first report, but in addition to villages like Surit, Beit Awwa, Beit Mirsem and El-Shuyoukh in the Hebron area and Jiflik, Agarith and Huseirat, in the Jordan Valley. The Special Committee has ascertained that all these villages have been completely destroyed Para 58. the village of Nebi Samwil was in fact destroyed by Israeli armed forces on March 22, 1971.

- ↑ "UNRWA's Frequently Asked Questions under "Who is a Palestine refugee?" begins "For operational purposes, UNRWA has defined Palestine refugee as any person whose "normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict." Palestine refugees eligible for UNRWA assistance, are mainly persons who fulfill the above definition and descendants of fathers fulfilling the definition."". United Nations. http://www.un.org/unrwa/overview/qa.html#c. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ "Note on the Applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees to Palestinian refugees". United Nations. 2002. http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3da192be4.html,UNHCR. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ "A/2171". United Nations. http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/0e598b25ff3267e20525659a00735ea7?OpenDocument.1952 Annual Report of the Director of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency of Palestinian Refugees "Despite the evidence of statistics, movement occurs; the refugees migrate, often illegally, across frontiers; they emigrate in small numbers to other lands; they get jobs--and some lose them; they go off ration rolls--and some return to them; they are born in great numbers--and they die in lesser numbers. To increase or to prevent decreases in their ration issue, they eagerly report births, sometimes by passing a new-born baby from family to family, and reluctantly report deaths, resorting often to surreptitious burial to avoid giving up a ration card."

- ↑ Arlene Kushner (2004). [http://israelbehindthenews.com/pdf/UNRWA.pdf "United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East"] (PDF). Israel Resource News. http://israelbehindthenews.com/pdf/UNRWA.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ "Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees" (PDF). UNHCR. 1951 and 1967. http://www.unhcr.org/protect/PROTECTION/3b66c2aa10.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ Pinner, Dr. Walter (1959 and 1967). How many refugees? and The Legend of the Arab Refugees. McGibbon & Kee. pp. ?.

- ↑ http://www.arts.mc.gill.ca.mepp/new-prrn/background (Palestine refugee researchnet

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1233304645372&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FPrinter 'UNRWA staff not tested for terror ties' Jpost

- ↑ http://www.mepeace.org/forum/topics/fixing-unrwa-by-james-g Repairing the UN’s Troubled System of Aid to Palestinian Refugees

- ↑ ABU TOAMEH, KHALED (20 July 2009). "Amman revoking Palestinians' citizenship". The Jerusalem Post. http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1246443863400&pagename=JPost/JPArticle/ShowFull. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ "Israel: We 'won't make Jordan Palestine'". The Jerusalem Post. 12 August 2009. http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1249418582807&pagename=JPost/JPArticle/ShowFull. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ↑ http://www.unhcr.org/news/NEWS/4919b20b4.html

- ↑ Poverty trap for Palestinian refugees By Alaa Shahine. 29 March 2004 (aljazeera)

- ↑ Lebanon permits Palestinians to work June 29, 2005 (Arabicnews)

- ↑ Exiled and suffering: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, 17 October 2007 web.amnesty.org

- ↑ Simon Haddad, The Origins of Popular Opposition to Palestinian Resettlement in Lebanon, International Migration Review, Volume 38 Number 2 (Summer 2004):470-492. Also Peteet [2].

- ↑ Mroueh, Wassim (Wednesday, June 16, 2010). "Parliament divided on granting Palestinian rights". The daily star. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/article.asp?edition_id=1&categ_id=2&article_id=116032#axzz0r0ZmfbZJ.

- ↑ http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/043/65/IMG/NR004365.pdf?OpenElement

- ↑ http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Peace%20Process/Guide%20to%20the%20Peace%20Process/Declaration%20of%20Establishment%20of%20State%20of%20Israel

- ↑ Ilan Pappe, "The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine", page 110

- ↑ http://www.thejerusalemfund.org/ht/display/ContentDetails/i/2591 "Under the laws of nationality and state succession, newly-created states are obligated to grant all persons found within the territory the nationality of the new state" http://www.palestinechronicle.com/view_article_details.php?id=14921 "Palestinian refugees were excluded from entitlement to citizenship in the State of Israel under the 1952 Citizenship Law. They were “denationalized” and turned into stateless refugees in violation of the law of state succession.". "The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine", Ilan Pappé, page 131

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ SAYYED, TASHBIH (JUNE 18, 2003). "Defeat Terrorism First". National Review. http://article.nationalreview.com/269137/defeat-terrorism-first/tashbih-sayyed. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ↑ "Yearbook of the United Nations 1948-49 (excerpts)". UNISPAL. 31 December 1949. http://unispal.un.org/unispal.nsf/361eea1cc08301c485256cf600606959/2dac0ed54bcd6af68525629f00718b98?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ "United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194" (PDF). United Nations. 1948. http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/043/65/IMG/NR004365.pdf?OpenElement. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ R. Brynen, 'Addressing the Palestinian Refugee Issue: A Brief Overview' (McGill University, background paper for the Refugee Coordination Forum, Berlin, April 2007), p.15, available at http://prrn.mcgill.ca/research/papers/brynen-070514.pdf (08/08/09)

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/middle_east/israel_and_the_palestinians/key_documents/1682727.stm Oslo Accords Declaration of Principals

- ↑ http://www.ynet.co.il/english/articles/0,7340,L-3558676,00.html 2nd Intifada forgotten

External links

See also

- Arab-Israeli conflict

- Estimates of the Palestinian Refugee flight of 1948

- Jewish exodus from Arab lands

- Jewish refugees

- List of villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war

- Palestinian diaspora